The Heruli Tribe of Scandinavia

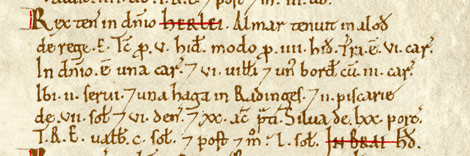

The original land in England that the Erleigh family took their name from was called “Herlei” (Latin name) as recorded in the Domesday Book in 1086 AD.

The English “Erleigh” family took their name from this land.

The English “Erleigh” family took their name from this land.

Was the land named “Herlei” because that was the name of the people (tribe) who settled there?

Origins of the Scandinavian Heruli Tribe

There is an early Proto-Germanic tribe that later came to be called the Heruli (or Herules), who arrived in Scandinavia possibly as early as 800BC. The Heruli are also referred to as the Herull, Heruls, Herulos, Harudes, Heroli, Hari, Harri, Eorle, Eruli, Erils, Aeruli, Iruli, Herouloi, Erouloi, Airouloi, or Ailouroi in the Greek.

There is no specific “Heruli” tribe or people are mentioned by name in the early Anglo-Saxon, Frankish, or Norse chronicles, so they may have been originally known in the north and west by another tribal name.

The Germanic tribal name Harjilaz, Herilaz, or Erilaz (theoretical plural, Heruloz) means “belonging to the marauders/harriers” [harji, from the Proto-Indo-European /koros/, means marauder/raider/harrier and ilaz, which is a suffix meaning “belonging to” (synonymous to -ling in Modern English, i.e. earthling);

Historians Pliny and Tacitus (circa 95 CE) both mention Suebian tribes called Harii or Hirri. That the Harii and the Heruli are basically synonymous is strongly evidenced by the fact that later in the 4th century AD Silinga, daughter of the last Heruli king Rhodoulph (“Honor-Wolf”?), who married Wacho, king of the Lombards (died 539), as his third polygynous wife, she named her son by him Walter (“Walt-Hari”, “ruler of the Hari/marauders”). From this, we can infer that the last known Heruli princess clearly believed that her royal son was “ruler of the Hari”, speculatively equating the Heruli with the Hari. In addition, the Histories of Agathias mention that a Heruli leader was named Phoulkaris (Greek) or Folk-Harjiz, again with the “hari” element found in a Herulian name.

Encyclopedia Britannica 1911 suggested that, since the name Heruli itself is identified by many with the Anglo-Saxon eorlas (“nobles”), 0ld Saxon erlos (“men”), the singular of which (erilaz) frequently occurs in the earliest Northern inscriptions, that “Heruli” may have been a title of honor within many tribes and not a tribe itself. If this is the case then this may be the reason that they are not mentioned as a “tribe” in the earliest records. There is even speculation that the Heruli were not a normal tribal group but a brotherhood of mobile warriors, though there is no consensus for this proposal, which is based only on the name etymology and the reputation of Heruli as soldiers.

Greek historian Jordanes in the 6th-century AD does mention in his description of the peoples on the island of “Scandia” that the Dani expelled Herulos from their settlements – perhaps in Scania, Halland, Blekinge or Sjælland, possibly around 200-300 AD. We know that around 200 AD Heruli warriors began to branch out and leave their Scandinavian homeland and conduct raids. Much like the Vikings who much later in history did the same thing, the Heruli ventured into lands and conquered and plundered.

While their name in history is somewhat obscure, later inscriptions in Scandinavia which are sometimes attributed to them suggest that this fierce, warlike people were called the ‘lords’ (‘erilaz’ singular, later ‘eorlas’ or ‘lords’ to the Angles and Saxons who migrated to Britain, and ‘erlos’ or ‘men’ to the Old Saxons). Perhaps it was bestowed as an honorific due to their fighting abilities amongst their fellow Scandinavians.

Leaving Scandanavia and Heading South

In the 1st century, as the Roman army attempted to advance into the forests of southern and West Germanic lands across the Rhine, they displaced the people who lived there. These displaced people sought refuge by traveling further to the north. As they traveled to the North, they met resistance, which led to battles in the north with the people who already lived there. One notable example took place in Denmark around this time.

There is a historical record that says that the Heruli were driven out of their homeland (Scandanavia) by the Danes. It could have been this forced migration that displaced the Heruli and caused them to span out towards the south around that same time. The battles near Alken Enge are waged during this period in which major changes are taking place in Northern Europe due to the expansion of the Roman empire, which is putting pressure on the Germanic tribes. This results in wars between the Romans and the Germanic tribes, and between the Germanic peoples themselves. The Heruli could have been directly affected by the battle in Denmark, while the Chatti are the victims of a similar post-battlefield process themselves in AD 58.

By about 200 AD Heruli warriors were leaving their homeland and conducting raids and it seems that the core Heruli group followed and went southward and are found on the lower Elbe in this period. From there they head south-eastwards over the course of two generations or so, heading in the direction of the Black Sea. Some of the Heruli people may have also stayed in southern Scandinavia or traveled further north into Scandinavia.

Heruli are first mentioned by Roman authors as one of several “Scythian” groups raiding Roman provinces in the Balkans and Aegean, attacking by land, and notably also by sea. The Heruli thought of themselves as “wolf-warriors”, consecrated to the early Germanic wolf-god Wodan. Accordingly, the name seems transparent in Scandinavian as härjulvar, “harrying wolves”.

In late antiquity, the Gepids, Vandals, Rugii, Scirii, the non-Germanic Alans, and the actual Goths were all classified by Roman ethnographers as “Gothic” peoples, and modern historians generally consider the Heruli to be one of these groups. Zonaras specifically stated that the Heruli were of Gothic stock. The “Goths” is a collective term for various tribal groups referred to as “Gothic” peoples, which understood each other because of their shared Gothic language and culture.

Other ancient sources, including Zosimus and Dexippo, say that a group of Goths and Heluroi, around the year 200 AD, had left Scandanavia and sailed from Crimea across the Black Sea and captured the great city of Trebizond, from which they took a big booty and abducted a large number of prisoners. The same fate befell other large and splendid cities of Bithynia, like Chalcedon and Nicomedia. It is also said that in emperor Gallienus’ reign, 260-268 AD the Goths and Heruls sailed with a large fleet through Bosphorus and Hellespont. They plundered Athens and many other cities. They landed in Greece, where the campaign’s leaders began to quarrel among themselves, and one of the Heruli leaders named Naulobatus, went into Roman service, together with all his men. He was very well received by the emperor, who gave him the rank of consul. They were one of the many foreign tribes serving in the legions of the Roman army.

Fighting Romans and Joining Romans

Heruli warriors are mentioned in Roman historical records in the period of about 250 AD to 500 AD as fighting in battles both “with” the Romans and “against” the Romans. In his 6th century work Getica, the historian Jordanes, wrote that the Heruli had been driven out of their homeland in Scandinavia by the Danes.

This has been read as implying Heruli had their origins in the Danish isles or southernmost Sweden. The reliability and correct interpretation of this passage in the Getica is, however, disputed. On the other hand, his contemporary Procopius recounted a migration of a 6th-century group of Heruli noblemen to Thule (which for him, but not Jordanes, was the same as Scandinavia), from their “homeland” on the Middle Danube. Later, Danubian Heruli found new royalty among these northern Heruli. This account has been seen as implying an old and continuous connection between the Heruli and Scandinavia.

IN 267/268 AD the Peucini Bastarnae tribe is specifically mentioned in the invasion across the Roman frontier. Part of the barbarian coalition includes Goths and Heruli. This is the first Roman historical record of the Heruli, which has them occupying territory around the Meotic swamps, close to the mouth of the Tanais (Don). They and the Goths are classed by Rome as pirates who ravaged the coasts of Greece and Asia Minor.

The Eastern and Western Heruli Groups

By the end of the third century there appear to be two groupings of Heruli, one in Eastern Europe and one in the west. Mamertinus records an attack by Heruli across the Lower Rhine and into Gaul. The Heruli also raid into Iberia along with Alemanni and Saxons. The attack presents a hard-pressed Rome with some difficulties in fighting the attack, as the empire is also concerned with mounting an attack on a usurper in Britain. Some of the Heruli warriors confronted by Roman troops were defeated in AD 287, they were captured and then employed (conscripted) by Rome as mercenaries. Ammianus mentions the Heruli and the Batavi together as brother people. The latter are well known for their services as Roman soldiers in the second and third centuries, so ‘brother’ in this sense could mean fellow Germanics serving together in the army.

In the 6th century a Roman historian, Procopius, says that after a catastrophic defeat to the Longobards a very large part of the Heruli went back to Scandinavia in the 6th century, where they settled on the island of Thule, that is the Scandinavian Peninsula “near the Goths” or “opposite the Goths.” Therefore, we believe that the Heruli originally came from Scandinavia, but since they are not mentioned in the Scandinavian historical sources, they must have been originally known in Scandinavia under a different name.

According to Procopius, when the Heruli returned to Scandinavia in the 6th century they settled beside the Geats (Gautoi). The place where they are assumed to have resettled is in the provinces of Blechingia and Värend, two districts where the women had equal rights of inheritance with their brothers. Some noble Swedish families in the area also claim to be descendants of the returning Heruli. This may have been where the original Huruli people were from prior to 200 AD.

The Path of the Heruli to England

The Roman Empire’s Crisis of the Third Century, also known as Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis (235–284 AD), was a period in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed under the combined pressures of barbarian invasions and migrations into the Roman territory. With civil wars, peasant rebellions, and political instability (with multiple usurpers competing for power), There was Roman reliance on (and growing influence of) barbarian mercenaries known as foederati and commanders nominally working for Rome (but increasingly independent).

Around this time (250-287 AD) it is probable that groups of Heruli warriors were sent to England to bolster the Roman army and serve as Foederati. The term Foederati was used to describe foreign states, client kingdoms, or barbarian tribes to which the empire provided benefits in exchange for military assistance. The term was also used, especially under the empire, for groups of “barbarian” mercenaries of various sizes who were typically allowed to settle within the empire. The Romans had been using mercenary troops in England since the 1st century. As an incentive to join the Roman legions Rome gave land to Foederati troops after 20 years of service. These Heruli mercenaries after serving would have been permanently settled and given land in exchange for their military service.

In AD 211 – Britain was divided up into two separate provinces; the south was to be called “Britannia Superior” (superior being in reference to the fact that it was closer to Rome), with the north being named “Britannia Inferior”. London was the new capital of the south, with York the capital of the north. As the Heruli troops arrived they were strategically settled in the southern area with the Thames river being the northern boundary in order to deploy and attack or defend the southern Roman area known as “Britannia Superior”.

The area in Britain where the Heruli and other Germanic people were settled and given land, was from Reading and Silchester in the north to Winchester in the south. This became the seed of what later would become the Saxon Kingdom. Today there is a small village and large, rural civil parish in Berkshire, England called “Hurley” (Herlei in Latin) and a modern-day town to the east of Reading called “Earley”.